Every college business student learns tariffs are bad for economies that believe in free markets and competition. Every economics textbook charts out how tariffs suck money out of consumers' pockets. Every MBA class learns it and they even teach it at Wharton. So if there is any government leader out there who attended Wharton and is promoting tariffs, someone needs to verify your degree.

At first glance, imposing tariffs or quotas appear to be the perfect solution to get American industries back on track to prosperity, but the reality is that tariffs steal money out of consumers’ pockets by increasing prices, stifling creativity, rewarding inefficiencies and destroying the competitive drive that allows a free market economy to deliver cheaper, smarter and innovative products to you. If you skipped college or avoided a business degree, you missed the most basic economics course that explains why tariffs and quotas work in communist countries but never work in a free market economy. This article refreshes you on Econ 101 and explains why tariffs in America cost you over $70 billion every year.

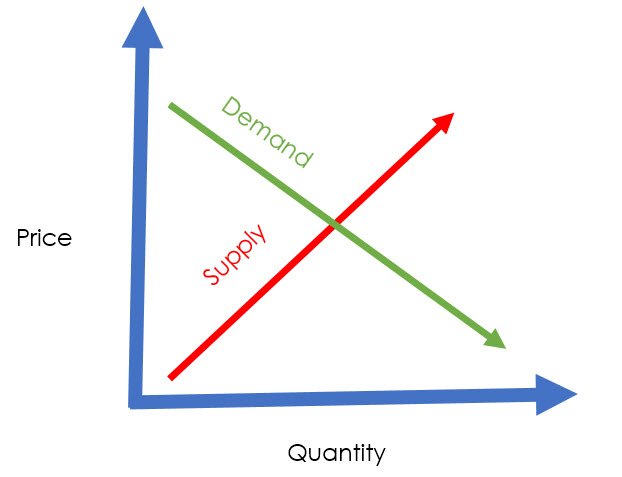

The price of a good is the intersection, or equilibrium, of the demand and the supply. The chart above illustrates the interaction between increased quantity and increased prices for buyers (demand curve) and suppliers (supply curve). The supply curve always rises since as prices increase, providers of goods want to sell more, and the demand curve always declines, since as prices rise, consumers always want to buy less. The intersection of supply and demand tells us the long term equilibrium of price and quantity.

A tariff is a tax on imports, paid to the government. Domestic producers are exempt from the tariff. A quota is a limit on the quantity allowed to be imported. The result of both is an increase in the price of the good, from the market price to the new tariff price. American manufacturers get to charge the new price, but manufacturers overseas receive the market price but pay the tariff to the US government. The government gains area “D” in the chart below (the revenue from the tariff); however, American consumers pay the higher price measured by areas A+B+C+D. Even if the government passes along to consumers the revenue from the tariff, the loss to consumers is still area B+D.

Tariffs and quotas are not sound public policy. The Congressional Budget Office's 95 page report explains in detail. And the Organization For Economic Cooperation and Development Report explains how our responses made things worse. And there is the Brookings Industry Report. Tariffs undermine competitive discipline which forces industries to always reduce cost and increase efficiency, driving creativity and invention. Protectionism has a narcotic effect, allowing sick industries to avoid facing up to their problems.

America has many precedents that teach us tariffs are bad policy, and the most obvious is the one industry promoted that tariffs will help today: steel. Going back 70 years, the steel industry was an oligopoly, with just a few manufacturers and little competition, allowing the industry to raise prices 9% annually in the late 1940’s (twice the rate of wholesale prices). In the early 1950’s, steel prices increased 4.8% annually at a time when the wholesale price index was falling. In the late 1950’s, steel prices increased 7.1% annually, three times wholesale prices. In 1969, quotas were imposed and steel prices increased 14 times greater than they had in the previous 9 years, during a time of recession and 25% of industry capacity in an idle state. The result was a lag in technology. American steel companies failed to introduce the oxygen process and continuous casting which put them at a disadvantage. Their oligopolistic pricing policy kept American companies from competing in the world market and eventually allowed imports to erode their market by producing a better product at a lower price. We can learn from history that tariffs are as un-American as you can get.